Ludwig van Beethoven spent most of his most productive compositional life battling a slow losing battle with deafness. He was an iconoclast of the first order, always choosing the difficult or unconventional path. That was true in all his compositions, most markedly in his more mature works. He wrote only seven concerti, one violin concerto, five piano concerti, and a triple concerto for piano, violin and cello. In this blog I will be focusing on his violin concerto. I will continue with his last two piano concerti in the following blog. All were written during his middle period, which also saw the composition of his great symphonies 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7, his middle string quartets 7 through 11, his only opera Fidelio, and his great piano sonatas 21 and 23, the Waldstein and Appassionata, among many other great compositions. This period began in 1802 when at the age of 32 he considered suicide because of his deafness. His decision to instead fight for his compositional art led Beethoven to enter a new era of compositional maturity, which began his most productive, middle period.

The Violin Concerto

Beethoven’s Violin Concerto ranks with the Brahms Concerto as the finest of that form. Like many of Beethoven’s works, the Violin Concerto was not received well at its premiere in 1806, and did not receive recognition until 1844, well after Beethoven’s death, when it was played by the 12 year old Joseph Joachim (the same Joachim for whom Brahms wrote his violin concerto) with Felix Mendelssohn conducting. From that time, Beethoven’s Violin Concerto has been a staple of the concert repertoire and has been recorded many times. Beethoven wrote the concerto for the violinist Franz Clement who did not possess a powerful tone, but instead could play the most difficult passages in the highest registers of the violin with perfect intonation. That explains the beautiful long lyrical passages that mark the first and second movements and the lack of bravura throughout the concerto. The concerto begins with a five note drum beat introduction by the timpani which will form the rhythmic basis of the first movement as well its harmonic invention. The first movement is structured as a conventional double exposition sonata form, where the orchestra plays its exposition, followed by the violin. However, Beethoven makes a major modification to the second exposition, nearly doubling its length. Instead of completing the exposition with a coda after the second theme, he abruptly starts a new modulating bridge and repeats a new version of the second theme and coda. The total length of the first movement is about 25 minutes in the average performance, about as long as the longest entire violin concerti written to that point. The Second movement, a lyrical modified theme and variations and third (rondo)and last movements are played without pause, unusual in standard practice of the time, but similar to his fifth and sixth symphonies and his fourth and fifth piano concerti. As was typical of earlier concerti, Beethoven did not write a cadenza for the first movement, letting the violinist improvise or choose a cadenza. There have been many different cadenzas written, the most popular by Joachim, Leopold Auer and Fritz Kreisler.

I grew up with Jasha Heifetz’s recording with Charles Munch and the Boston Symphony on RCA. Like Heifetz’s recording of the Brahms Violin Concerto it is an early stereo recording recorded in 1955, one of the best of RCA Living Stereo recordings. Compared to other violinists, Heifetz’s tempi are much faster. In fact, his first movement timing is about 5 minutes or 20% shorter than the average. So there is a pulse to the music that other performances lack, or a lack of relaxation and serenity of other performances. Heifetz is a must, but you should have another version also.

The early EMI Columbia recordings have two of the great performances, by Russian violinists David Oistrakh and Leonid Kogan. Both are available in modern vinyl reissues on Testament as well as earlier reissues on EMI. Kogan’s is a lyrical, beautiful recording. Oistrakh keeps the same measured tempo as Kogan, but his playing is more magisterial, and a bit less lyrical. Both are excellent alternatives to Heifetz The reason I emphasize the reissues is that original issues of the Kogan and Oistrakh have become very expensive on the used market. The Oistrakh was over $500 in 2016, and the Kogan (along with many of his other recordings on Columbia SAX,) has reached the stratosphere, with $5000 an average price in 2016. The photos I show are of the fine Testament reissues. Kogan’s version is also available on the new Electric Recording Company label. ERC specializes in very limited productions of selected rare and extremely valuable EMI recordings, using carefully restored vintage tube equipment for mastering and cutting the vinyl and high quality letter press album covers. They price their reissues for the collectors market, current prices are around 450GBP (in early 2017). Recently (Feb 2017) High Definition Tape Transfers (www.highdeftapetransfers.com) has issued the Oistrakh in digital from a 15ips 2 track tape. I was very pleased with the DSD256 version. There are also versions at lower resolution in DSD, DXD and PCM.

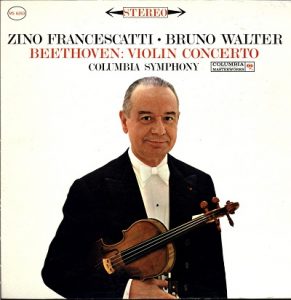

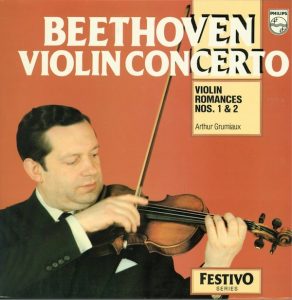

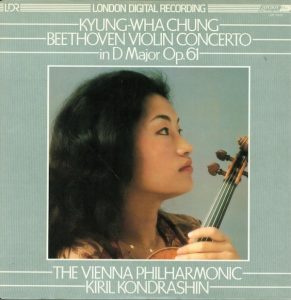

There are many other fine recordings of the Violin Concerto. In my collection I am singling out three. The first is by the great French violinist Zino Francescatti with Bruno Walter conducting the Columbia Symphony Orchestra (Columbia MS6263). In addition to the Heifetz recording mentioned above, this is a recording that I acquired in college and played often. It contrasts with the Heifetz in its great lyricism. Francescatti and Walter are also featured the the Brahms Double Concerto which I discuss in another Blog. The other two recordings are by the great Belgian violinist Arthur Grumiaux on Philips (I have the Philips Festivo reissue) and an early digital recording by the wonderful Korean violinist Kyung-Wha Chung on Decca/London. We heard Chung in a solo recital in London in 1985, five years after doing this recording.